Antonioni's Blowup takes a murder mystery premise and cleverly subverts it. It concerns us with a fashion photographer in the London of the Swinging Sixties, Thomas (David Hemmings), who happens to think he has witnessed - accidentally captured on camera - a murder. And then it abandons the narrative necessity to "solve" the case: instead telling us that we can't be too sure that we saw something (recalling Heisenberg's principle more than anything else).

The film is permeated by a sense of sly humour. An early scene captures Thomas doing a photo shoot with real-life fashion model Veruschka, and Antonioni plays out the scene with a strong subtext of sexuality. It is as if the photographer and model are engaging in virtual intercourse; complete with lines like "now give it to me, really give it to me, my love" and a mock-up of post-coital exhaustion. Much of Veruschka's sensuality is coldly calculated. Glossy surfaces housing empty beings - Antonioni's major theme, the connecting-thread in his whole body of work.

Thomas wanders into a park, sees an unlikely couple - a middle-aged woman with an elderly man - and out of both boredom and voyeuristic curiosity starts shooting them. The woman (Vanessa Redgrave) notices, comes to Thomas and demands that he hand over the roll of film to her.

He refuses, promises to send her the photos later. He is followed back to his studio by the woman. She repeats her request, even makes a sexual advance as 'payment', but is interrupted. Interruptions are the film's building blocks. Antonioni's characters don't really have deep-seated motives, a philosophy to live life by. They're empty pages coloured with fancies as they come.

Thomas goes to nightclub where The Yardbirds are playing. Jeff Beck's guitar processor starts malfunctioning; in a fit of rage he breaks his guitar (mimicking the antics of Pete Townshend) and throws the broken fretboard to a rapturous, drugged crowd. There is much pushing and shoving as fans try to get this souvenir. Thomas grabs it, runs outside and throws the fretboard on the pavement. A fellow standing nearby picks it up, examines it (of course, not knowing that it is Jeff Beck's) and throws it down again. Two points to note: 1) Thomas really had no reason to grab and run away and just did it to disappoint the others, and 2) that a thing, once stripped from its context, does not convey any meaning. The first gives us a guide to understand the psyche of Antonioni's characters (Jack Nicholson in The Passenger decides to exchange his identity with a dead, similar looking man without any apparent motivation). The second gives us the thumb-rule to understand his films. There is hardly any sequence in an Antonioni film that would stand on its own merit - you cannot talk of scenes unless you connect it with the others.

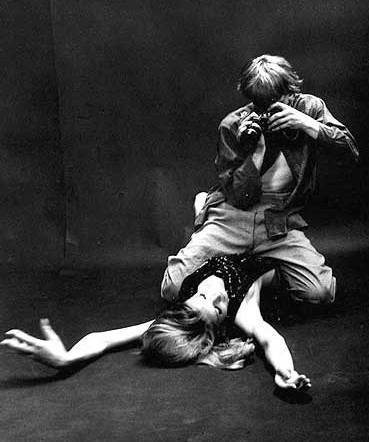

The woman (Vanessa Redgrave) who wanted the roll of film back visits Thomas. He hands her a fake and develops the photographs he took in the morning. As he pins the photos side by side and examines them he thinks he has unwittingly caught a man being shot down. To get a clearer look he blows up a part of the image. There's a lot of noise - graininess - so we can't be exactly sure. He seems quite certain though.

The mise-en-scene here deserves special mention. A photo of the woman looking away while she embraces her lover becomes a sort of reaction shot.

But whereas the reaction shot is traditionally used to reinforce the illusion of reality*, Antonioni subverts by not clearly showing the object that draws her attention. The camera pans from the still (shown above) to the wall where a blowup of the fence she seems to be looking at is pinned. (Illustrated in the following screenshots)

The resulting visual joke is that the woman is looking from the confines of her photo to the bush and fence shown in the adjacent photo. But we still can't see what she's been looking at**. The other - larger - subversion here is of a close-up. Originally the close-up was invented because objects could not be fitted completely into the aspect ratio of the frame. Hence a part of the object or person was shown, and the camera was sometimes moved to capture the whole part by part. This largely worked as a synecdoche (i.e. the part representing the whole). But whereas the classical close-up clarified or emphasized intent, Antonioni's close-up says that the deeper we try to go the more the object of our concern disintegrates ("blowing up" in a deliciously ironic sense). It also serves as self-criticism: Antonioni's films being basically probing character studies done in a minimalist manner.For some inexplicable reason, Antonioni actually shows a gun sticking out of one of the bushes, and later, a corpse lying beside a hedge when Thomas revisists the park in the night. Which seems strange given that Antonioni has been trying to bury the deterministic trait in classical literature and cinema uptil this point. (An alternate reading might be that Thomas really did spot the truth but has no concrete irrefutable evidence to back his discovery.)

Perhaps this is overcome, and explained, by the celebrated finale. A group of anarchic teenagers, dressed as harlequins, show up the film at several points. This group now arrives at a tennis court just outside the park which was the "crime-scene". They mimic a game of tennis. But between themselves the excitement and enthusiasm in this make-believe game is real, as is their match. Thomas looks on, amused. Then the invisible ball gets out of court and the players insist that Thomas throw them the ball.

Now that he has participated in their make-believe, he can hear the sounds of the tennis ball hitting the ground and the rackets (before this, the match is played out in silence). This is unusual given that the film never uses non-diegetic*** sound except in this scene. All of Herbie Hancock's wonderful jazz score can be heard only when the radio or the record player is on. Antonioni's daring use of sound makes us conscious of the illusory nature of cinema: which resembles and comes to life (the non-diegetic becoming diegetic) only when there is communal participation and suspension of disbelief (in the cinema theatre).

The final sequence of the film shows, in a long shot, Thomas standing in the field. His image slowly fades away. Thomas is unreal - a character in a make-believe medium. The camera lies. Did Thomas' camera lie too? And does Antonioni's camera lie when it shows us the corpse?

Footnotes:

*A typical Hollywood trope is to cut next to a POV - if one shot shows A (in the frame) looking at B (out of the frame), the next shot shows B (now in frame) from A's perspective.

**The viewer who wants to see for himself if there was a murder or not must understand that the photographs are taken from a single point in the park - where Thomas was hiding behind a tree - and that is our reference to determine directions.

***In simple words, diegetic music/sound is one which is being played in the space being exhibited, i.e. the music/sound belongs to the "world" of the film/play. Non-diegetic is when the sound does not belong to the space in focus.