An

invisible prowler peeks in through the windows of a girls’ dorm. A girl having

sex sees him, but her partner can’t. The prowler enters the corridor of the

dorm, passing by several girls, none of whom notice him. He briefly enters the

room of a girl pleasuring herself, then goes to the shower. The room is steamy.

We briefly see this spectral presence reflected in the mirror, knife in hand.

He parts the curtain behind which a girl is showering. The girl sees him and

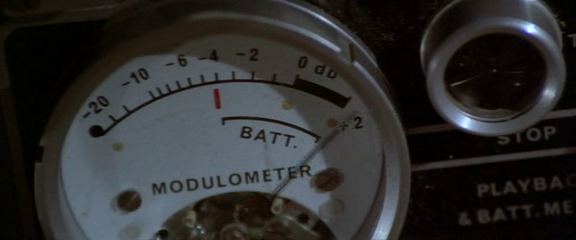

screams. Terribly. We’re now in a projection room. A B-movie director is going

through the rushes of his latest sexploitation venture with soundman Jack Terry

(John Travolta). The wind needs to be redone, the director says. The stock sound

is so overused it’s insipid. And the scream has to be corrected, of course.

He

goes to a bridge on the river at night, to get new wind. As he moves the mike around,

recording, ambient noises rise and fall. The camera seemingly looks around, trying

to find the source of the dominant sound before finally focusing on it. The

serene uniformity of the soundscape – nothing particularly loud – is suddenly

broken when we hear an explosion and then see a car hurtling down into the

river. Every sound in this sequence is seeking its accompanying image – craving

diegesis – before finding it and giving way to the next sound. Only the fully

focused image of the source resolves the mini-pocket of suspense (“where does

it come from?”) built around a ‘floating’ sound.

Terry jumps

into the river and manages to rescue the girl in the passenger seat. The driver

dies. It is only later that he learns who the dead driver is – Presidential favourite

Governer McRyan, out for a fun night with a call girl. Convinced that the

accident is a cover-up for an assassination Jack takes it upon himself to find

and establish “the truth” – for which, he makes a sort of found-footage film

from his audio recording and stills of the incident published in a magazine.

De

Palma’s inspirations behind the film are well-known – Antonioni’s Blow-Up and Coppola’s The Conversation, as also the Zapruder

film – but his thrust is in a whole different direction. The question here isn’t

about the tendency of the medium to distort or hide the ‘essential information’

– like the noisy film stock/recording in Blow-up/Conversation¸

both of which become so open-ended when stripped down and amplified that one wonders

if the mind is imagining things. De Palma makes it clear that McRyan has indeed

been killed, so the drama for a good portion concerns the minutiae of Terry’s

amateur filmmaking. In a reversal of roles with the Zapruder film what exists

as primary document here is the sound of the incident. The image has to be

constructed for Terry’s claims to be substantiated. He succeeds, sure, but at

what cost?

What

Terry believes in, of course, is a variation of the old wisdom about film

editing – that it is only in the re-assemblage of shot footage that one finds

meaning (or “truth”). In a world of uncommitted dime-a-day shlock he’s the last

idealist, believing the medium must be put at the service of truth. What the guy

doesn’t know is the other old adage – you can’t be in the business without giving

up part of yourself. It is only through the loss of his naiveté – and the girl

for whom he staked so much – that he completes the only missing bit in the sexploitation

film: the scream. The relation has finally been reversed – if much of the film

was a search for the perfect image by sound, the denouement has an image find the perfect

sound it was looking for all along.