My

Name is Nobody (Tonino Valerii/Sergio Leone, 1973) sits at all sorts of strange intersections: between comic and serious spaghetti

westerns (the former typified by the Trinity series starring Terrence Hill, ‘Nobody’

in this film); between the old West of Henry Fonda’s idealism and the post-modern

West of endless cultural references and tropes; but most crucially the

intersection in a dark movie theater of a star and his awestruck fan.

|

| From which came the Wild Bunch. |

Fonda

plays Jack Beauregard – aging, conscientious gunslinger who draws so fast that

he can fire three shots in the space of one. A hero of the Old West, a ‘national

monument’, he’s the star of Nobody’s eyes. Nobody is a comically fast draw (who, in deference to his idol, never exhibits his tact before Beauregard),

Trinity wandered into the wrong set. He knows Beauregard’s exploits by heart (“82

was one of your best years”) and wants to see him go out with a bang against

the infamous Wild Bunch (“150 who shoot and ride like there's thousands”). So

he dogs Beauregard’s tracks and practically coerces him into a showdown.

The movement

here practically plays as a riff on fan-culture myth: the movie star a graceful,

kind fellow with super-powers; the star’s heroic exploits in movies (where the star and the character can never be separated) and the fan's own dream scenario starring the hero pitted against villains.

Hero-worship,

however, is no one-way street. The dreamer fashions himself after the star:

practicing his swagger in front of a mirror and, at least in his subjective estimation, outdoing him. The fan is a self-appointed successor to the hero,

the one who inherits his legacy and displaces him.

|

| Wearing the hero's hat. |

It is then entirely fitting that the star has to enter the dream under the aegis of the devotee. The screen – the barrier between performer and spectator – dissolves. The kid in the theater

saves his idol from a rut and gives him the perfect alibi for a peaceful

after-life. A final gambit. Death in the space of the movie.

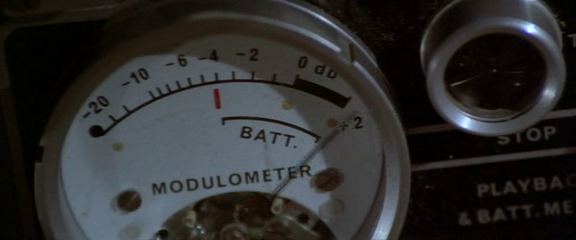

To be staged in front of an audience, with a camera recording the proceedings for

eternity (the players being asked to re-position to fit into the camera's frame).

In the

after-life, three days after his ‘death’, the superstar writes a letter to his

fan – thanking him for the trouble taken, for the favour done, noting how

Nobody’s finally a Somebody, a standout from the crowd in the theater. The

dream has been played out, the payback delivered. The star will ride

out in a ship called 'The Sundowner' and the kid will take his position.

Post-scripts

The aspect ratio of frames, wherein the meta-myth is constructed.

|

| The old hero looking at himself in a 4:3 mirror: the frame of classic westerns. |

|

| The new hero in his Cinemascope frame. |

|

| The new hero displacing the old in the same space: the barbershop (refer first still in this triptych) and its old-time 4:3 mirror. |