Courtesy Zee Studio, I got to see this timeless classic by Satyajit Ray this Sunday. And inspite of the examinations looming over my head, I just can't suppress the urge to have my say on the movie.

Ray's third film, and the final instalment of the Apu Trilogy, begins with a portrayal of Apu staying in a rundown shabby quarter in Kolkata. He has no fixed job, just a few tuitions thrown here and there to earn himself enough money to have a meagre meal each day. Apu also writes an occasional short story and sends it to literary magazines-- and that's what pleases him most about his life. Even in this life of extreme poverty and deprivation, nothing can suppress his indomitable, and yet apprehensive and shy, spirit-- he has not lost his dreams of becoming a great author. When Pulu, Apu's best friend, arrives and offers him assistance in finding a fixed job, Apu expresses his dissatisfaction over the idea. Apu has realised that his life's goal is to remain free and thoughtful-- not bound to a job he doesn't like doing (he quotes names of great men who never once in their life 'settled down', to prove his point). Nonetheless Apu agrees to go to Pulu's mamabari (maternal uncle's house) at Khulna with him for Pulu's cousin's wedding ceremony. On the way to Khulna, Apu shows Pulu the manuscript of a novel he has started writing-- a work of art that Pulu admires quite a lot after giving a read. However on Pulu's cousin, Aparna's, wedding-day, it's revealed that her bridegroom is mentally unstable. Aparna's mother disagrees to surrender her daughter to a madman. In a strange turn of events, Apu somewhat unwillingly yields to the pressure of marrying Aparna-- for if he refuses, no one shall ever marry her again. On their first night together, Apu openly talks to his new bride, and honestly says that he is nothing more than a poor, thoughtful man with a penchant for writing stories-- who has nothing more than a few pennies and a ramshackle quarter to his name. Apu says that Aparna may have to adjust to living such a deprived life. Aparna willingly accepts her fate-- determined to be happy even amongst such poverty.

When Aparna is brought to Apu's Kolkata quarters, she suddenly realises the magnitude of his poverty-- and the hardships that await her. But as she gazes down the window through tearful eyes, she sees a poor child smiling and playing on the street with his mother-- and this cheers her up. Apu understands how hard it must be for Aparna to see the sharp contrast in lifestyles-- but when he asks her about the same, he is greeted with a warm smile, which reflects the love and respect Aparna has for Apu, and also the readiness with which she accepts her new life. Special credit must go to Satyajit Ray here for a cinematic metaphor which only geniuses can conceive-- in place of Apu's erstwhile tattered and dirty window-curtain hangs a clean one. The visually improved condition of Apu's household couldn't be portrayed better. There hasn't been much financial betterment since his marriage, but Apu's life has become more arranged, orderly and beautiful-- something which only a soft feminine touch of care and concern can bring about. After several blissful months together, Aparna leaves for her maternal home due to pregnancy. In the following two months, Apu and Aparna exchange warm letters of love-- their craving for each other almost seems childish at times. Apu's promise to visit her at the end of the month remains unfulfilled however-- while delivering their child, Aparna dies due to labour pains. Apu is so much aggrieved to hear the news that he can't stand the truth anymore-- in a trance of unspoken and unbearable pain and sorrow, he leaves Kolkata and wanders on meaninglessly. Suddenly, Apu's life and love lose all meaning to him-- he throws away the manuscript he so thoughtfully and carefully wrote at one point of time.

Several years pass by, and in the meantime Apu and Aparna's son Kajal grows up in the Khulna-house under the care of his maternal grandparents. The little child is just like his father-- carefree, imaginative, capricious and endearing. Aparna's father soon develops a grudge against Apu-- he can't bear the fact that a father never once came to take his son with him. Even the child, named Kajal, starts regarding his father with contempt-- people taunt him due to him being practically 'fatherless'. Pulu, Apu's old friend, comes back to Khulna from abroad and finds the house in a poor state-- his mama is old and nearing his end, while Kajal remains 'fatherless' and uncared for by the old man (who naturally can't run after the naughty child and cater to all his childish whims!). Incidentally, Pulu discovers Apu in the vicinity of Khulna and learns that Apu has been doing a job to somehow sustain himself. Apu is torn between his pain due to the loss of his beloved Aparna and his duty towards his son-- he can't stand the fact that he has to love a child whose birth resulted in the death of his beloved wife. (This explains Apu's negligence towards his child.) Apu therefore requests Pulu to arrange for his son's education in some boarding school, the expenses of which he is ready to bear. Because Pulu is in a hurry to leave the place and can't keep his friend's request, as a last plea, he urges Apu to visit the Khulna-house once and at least see his son for one time. Somewhat unwillingly, Apu does so. But when Apu sees Kajal, he discovers an affection for the boy hidden in some obscure corner of his heart and overshadowed by his immense bitterness towards his fate-- but on the contrary, Kajal is not ready to accept his father's affection. Touchingly, Apu presents his son with a toy-train (those who remember Pather Panchali remember how both Apu and Durga were fascinated with trains as children), but the child throws the gift away. Just when Apu is about to leave the place, broken-hearted for a second time, Kajal hesitatingly asks if Apu is ready to take him to his father in Kolkata (which actually shows that Kajal doesn't actually believe that Apu is his own father, but still touchingly discovers love for Apu too-- if not a father, Apu still is a close friend to the little one).

The film, quite simply, is poetry on celluloid. Ravi Shankar's touching sitar chords and the brilliant camerawork only make the film better. All the actors, and especially Soumitra Chatterjee and Sharmila Tagore (for both it was a debut-- and a debut couldn't have been better!), deserve plaudits for their natural and superb performances.

Again, some of my favourite scenes in the film deserve special mention. When Apu and Aparna come back from the theatre in a horse carriage, Apu stares at his beautiful wife's expressive eyes and lovingly asks "Tomaar chokhe ki aachhe?". With a charming glint in her eyes, she evades the real essence of the question, and answers "Kajal". And hence the name of their child-- the fruit of their immense but short-lived love-- finds a special meaning.

A second favourite scene would be the one in which Apu tries to befriend a reluctant and bitter Kajal, in the same room in which he had first talked his heart out to Aparna. The expression on Apu's face as Kajal threw the toy-train away in anger reflects how hurt he is-- a symbol of his love (both for his child, and for his lifelong fascination: trains) is so hastily dismissed by his own son.

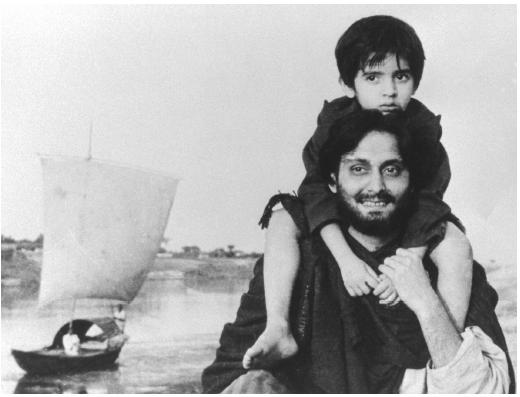

The final scene is perhaps the grandest one: Apu gets his son-- the last physical manifestation of his undying love for Aparna, Kajal not only finds his father but a close friend, and Aparna's father sees his little dream of Apu and Kajal staying together come true-- he smiles as he sees father and son go away to their land of dreams. What happens thereafter to Apu and Kajal is left for us to imagine and decide.

Ray's third film, and the final instalment of the Apu Trilogy, begins with a portrayal of Apu staying in a rundown shabby quarter in Kolkata. He has no fixed job, just a few tuitions thrown here and there to earn himself enough money to have a meagre meal each day. Apu also writes an occasional short story and sends it to literary magazines-- and that's what pleases him most about his life. Even in this life of extreme poverty and deprivation, nothing can suppress his indomitable, and yet apprehensive and shy, spirit-- he has not lost his dreams of becoming a great author. When Pulu, Apu's best friend, arrives and offers him assistance in finding a fixed job, Apu expresses his dissatisfaction over the idea. Apu has realised that his life's goal is to remain free and thoughtful-- not bound to a job he doesn't like doing (he quotes names of great men who never once in their life 'settled down', to prove his point). Nonetheless Apu agrees to go to Pulu's mamabari (maternal uncle's house) at Khulna with him for Pulu's cousin's wedding ceremony. On the way to Khulna, Apu shows Pulu the manuscript of a novel he has started writing-- a work of art that Pulu admires quite a lot after giving a read. However on Pulu's cousin, Aparna's, wedding-day, it's revealed that her bridegroom is mentally unstable. Aparna's mother disagrees to surrender her daughter to a madman. In a strange turn of events, Apu somewhat unwillingly yields to the pressure of marrying Aparna-- for if he refuses, no one shall ever marry her again. On their first night together, Apu openly talks to his new bride, and honestly says that he is nothing more than a poor, thoughtful man with a penchant for writing stories-- who has nothing more than a few pennies and a ramshackle quarter to his name. Apu says that Aparna may have to adjust to living such a deprived life. Aparna willingly accepts her fate-- determined to be happy even amongst such poverty.

When Aparna is brought to Apu's Kolkata quarters, she suddenly realises the magnitude of his poverty-- and the hardships that await her. But as she gazes down the window through tearful eyes, she sees a poor child smiling and playing on the street with his mother-- and this cheers her up. Apu understands how hard it must be for Aparna to see the sharp contrast in lifestyles-- but when he asks her about the same, he is greeted with a warm smile, which reflects the love and respect Aparna has for Apu, and also the readiness with which she accepts her new life. Special credit must go to Satyajit Ray here for a cinematic metaphor which only geniuses can conceive-- in place of Apu's erstwhile tattered and dirty window-curtain hangs a clean one. The visually improved condition of Apu's household couldn't be portrayed better. There hasn't been much financial betterment since his marriage, but Apu's life has become more arranged, orderly and beautiful-- something which only a soft feminine touch of care and concern can bring about. After several blissful months together, Aparna leaves for her maternal home due to pregnancy. In the following two months, Apu and Aparna exchange warm letters of love-- their craving for each other almost seems childish at times. Apu's promise to visit her at the end of the month remains unfulfilled however-- while delivering their child, Aparna dies due to labour pains. Apu is so much aggrieved to hear the news that he can't stand the truth anymore-- in a trance of unspoken and unbearable pain and sorrow, he leaves Kolkata and wanders on meaninglessly. Suddenly, Apu's life and love lose all meaning to him-- he throws away the manuscript he so thoughtfully and carefully wrote at one point of time.

Several years pass by, and in the meantime Apu and Aparna's son Kajal grows up in the Khulna-house under the care of his maternal grandparents. The little child is just like his father-- carefree, imaginative, capricious and endearing. Aparna's father soon develops a grudge against Apu-- he can't bear the fact that a father never once came to take his son with him. Even the child, named Kajal, starts regarding his father with contempt-- people taunt him due to him being practically 'fatherless'. Pulu, Apu's old friend, comes back to Khulna from abroad and finds the house in a poor state-- his mama is old and nearing his end, while Kajal remains 'fatherless' and uncared for by the old man (who naturally can't run after the naughty child and cater to all his childish whims!). Incidentally, Pulu discovers Apu in the vicinity of Khulna and learns that Apu has been doing a job to somehow sustain himself. Apu is torn between his pain due to the loss of his beloved Aparna and his duty towards his son-- he can't stand the fact that he has to love a child whose birth resulted in the death of his beloved wife. (This explains Apu's negligence towards his child.) Apu therefore requests Pulu to arrange for his son's education in some boarding school, the expenses of which he is ready to bear. Because Pulu is in a hurry to leave the place and can't keep his friend's request, as a last plea, he urges Apu to visit the Khulna-house once and at least see his son for one time. Somewhat unwillingly, Apu does so. But when Apu sees Kajal, he discovers an affection for the boy hidden in some obscure corner of his heart and overshadowed by his immense bitterness towards his fate-- but on the contrary, Kajal is not ready to accept his father's affection. Touchingly, Apu presents his son with a toy-train (those who remember Pather Panchali remember how both Apu and Durga were fascinated with trains as children), but the child throws the gift away. Just when Apu is about to leave the place, broken-hearted for a second time, Kajal hesitatingly asks if Apu is ready to take him to his father in Kolkata (which actually shows that Kajal doesn't actually believe that Apu is his own father, but still touchingly discovers love for Apu too-- if not a father, Apu still is a close friend to the little one).

The film, quite simply, is poetry on celluloid. Ravi Shankar's touching sitar chords and the brilliant camerawork only make the film better. All the actors, and especially Soumitra Chatterjee and Sharmila Tagore (for both it was a debut-- and a debut couldn't have been better!), deserve plaudits for their natural and superb performances.

Again, some of my favourite scenes in the film deserve special mention. When Apu and Aparna come back from the theatre in a horse carriage, Apu stares at his beautiful wife's expressive eyes and lovingly asks "Tomaar chokhe ki aachhe?". With a charming glint in her eyes, she evades the real essence of the question, and answers "Kajal". And hence the name of their child-- the fruit of their immense but short-lived love-- finds a special meaning.

A second favourite scene would be the one in which Apu tries to befriend a reluctant and bitter Kajal, in the same room in which he had first talked his heart out to Aparna. The expression on Apu's face as Kajal threw the toy-train away in anger reflects how hurt he is-- a symbol of his love (both for his child, and for his lifelong fascination: trains) is so hastily dismissed by his own son.

The final scene is perhaps the grandest one: Apu gets his son-- the last physical manifestation of his undying love for Aparna, Kajal not only finds his father but a close friend, and Aparna's father sees his little dream of Apu and Kajal staying together come true-- he smiles as he sees father and son go away to their land of dreams. What happens thereafter to Apu and Kajal is left for us to imagine and decide.